I sometimes write songs, and this one is from a proposed EP being put together by some wonderfully talented friends of mine. The collection of songs for the EP has a very chilled vibe, somewhat post-punk, and my topics are offbeat. This song, Mughal Lovers, is based on a beautiful Mughal Indian miniature, the original of which hangs in the Museum Rietberg in Zurich. It was painted in Himachal Pradesh in about 1780-1790 in watercolour and gold on paper. In the song, I compare the painting's martial alarm with the pastoral peace of a Hindu watercolour from the same time and place, of Radha and Krishna in a forest glade, painted about 1775. Though the music has yet to be decided on, in my mind's ear, it is a stoner-doom track ;)

Mughal Lovers

© Michael Schmidt 2016

Mughal

lovers

on the verandah

They turn

at the

sound of thunder

Lightning

rips the

fabric of the air

His musicians play on

murali, tambura

and pakhavaj

while six white birds

like hooked crosses

flee the threatening sky

a lone white bird

flies instead to the west

Clutching

his hand

yet she is unafraid

Bring me

my sword!

Orange-robed

woman complies

Green hills

succumb to darkness

In a

forest

Krishna and Radha

frolic on

a bed of leaves

His Sahasrāra

spouts golden filaments

his blue right hand

deep in her yoni

Mughal

lovers

trapped in wonder

They turn

at the

sound of thunder

Lightning

rips the

fabric of the air

He must go off to war

but Krishna and Radha

are rolling on the floor

Mughal

lovers

Mughal

lovers

Mughal

lovers

huh!

[ENDS]

Tuesday 24 October 2017

At the Confluence of Desire & Power

The reviewers, James D Sidaway and Richard J White, write about Kropotkin and Reclus: "Arguably their commitment to writing geography was a means to promote popular appreciation of the diversity of culture, nature, and society without hinging this directly to imperial and racial theory." Because of course, cartography as a modern discipline was grounded in racist imperialism - with the anarchists providing a much-needed libertarian alternative.

One of the criticisms of my book Cartographie de l'anarchisme révolutionnaire (Lux Éditeur, Quebec, 2011) that really touched me was that it was pretty poor on the actual cartography, the reader having desired graphic maps of the movement, not mere verbal descriptions. I partially rectified that in the English-language edition, but I hope to do far better service to the study of class geography with my forthcoming works, in particular the multimedia project On the Waterfront: Anarchist Counter-power in Port City Littorals which maps dockside community politics in Buenos Aires, Cape Town, Santos, Barcelona, San Francisco, Tampico and Berdyansk.

Looking at the 2008 world map made of waste paper by artist Vik Muniz below reminded me of the stunning 2006 birch-wood sculpture by Maya Lin of the depths of the Caspian Sea, its surface bent by the curvature of the earth. All this thinking on how infinitely flexible map-making can be reminded me of a piece I wrote that was published in the pan-African journal Ogojiii last year (below).

Map-making has always been and still remains as much an exercise of fantasy as it is of fact, and Africa’s vast expanses have drawn cartographers as the Bermuda Triangle draws doomed ships

The earliest maps were crudely linear in that they merely charted important trade routes, and were not concerned with the perilous hinterland or with establishing a holistic, interconnected view. The earliest surviving map rendering the entire continent in very rough outline is the Kangnido Map, a schematic 1402 Korean chart of the known world that shows Africa as a distended balloon like the udders of an Nguni cow.

Humourist Terry Pratchett noted that “cartographers get embarrassed about big empty spaces”, so early maps of Africa tended be crammed with fanciful tribesmen and mythic kingdoms: Sebastian Münster’s squarish 1554 chart features the one-eyed giant Caliban, and the fabled realm of Prester John.

Once the circumnavigation was mapped, it was initially only as an interlinked series of coastal features intended as a linear guide for trading ships. It was still some centuries before the outline familiar to us was represented in the 1584 map of Dutchman Abraham Ortelius.

But Ortelius’ image was incorrect as he used a cylindrical map projection developed by Flemish cartographer Gerardus Mercator in 1569. Nicholas Crane in his book on Mercator exclaimed that “maps codify the miracle of existence,” but while Mercator is of use to navigators, it distorts landmasses as one moves towards the poles, so Greenland is shown as larger than Africa, which is in fact 14 times its size, while the Cahill-Keyes Projection published by Gene Keyes in 1975 boasts minimal distortion.

“Before maps,” wrote Tanzanian novelist Abdulrazak Gurnah, “the world was limitless. It was maps that gave it shape and made it seem like territory, like something that could be possessed…” From the 1737 map by German mathematician Johann Matthias Hase which delineates imaginary territories such as “Ethiopia Inferior”, a huge arc from Mauritania to Uganda, to contemporary artist Wolfwoman7’s Africa Map made of various animal hides, maps have attempted to transform the illusion of possession into something tangible.

A bid at realism that was also hopelessly wrong was John Cary’s 1805 chart, which shows only the polities then known to Europeans, but also a “Soudan” that runs across the entire Sahel, bounded on its south by a continuous chain of fictitious mountains, with the sub-Saharan interior tersely labelled “Unknown Parts”.

It was that tantalising unknown that drew David Livingston, Richard Burton, Johan Hanning Speke, and Henry Morton Stanley to venture forth, resulting in the 1880 map by Eugène Andriveau-Goujon – recognisably modern and near-complete in terms of its geographic features, an accuracy that would be exploited five years later as the Scramble for Africa began.

So cartography is ultimately about the confluence of desire and power – and here are four cartographic attempts at balancing those imperatives in very different ways:

Speculation: the 1402 Yi-Kwon Map

Despite its many obvious errors, including the absorption of almost the entire interior into a giant version of Lake Victoria, the “Kangnido” map by Yi Hoe and Kwon Kun at least showed that the Koreans knew – via Islamic traders – that the Nile originated in a great lake and emptied into the Mediterranean, though Africa’s outline is hugely speculative. But the map is striking because it was produced a full 95 years before Bartolomeu Dias and Vasco da Gama rounded the Cape in 1497. The almost identical Chinese Da Ming Hun Yi Tu Map is claimed to date from 1389 though this is disputed. In his bestselling but academically contested book 1421, Gavin Menzies theorised that the Kangnido Map originated in a Chinese rounding of the Cape in 1421, and he adjusted the map (at right above) for longitude, restoring West Africa’s prominent bulge.

Subversion: the “1844” Cyon Map

Swedish artist Nikolaj Cyon drew an alternative map of Africa – which he renamed Alkebu-Lan, or Land of the Blacks in Arabic – as it would have looked in the year 1844 as an experiment in an alternative world timeline in which the Black Death almost wiped out the population of Europe, leading to a Muslim rather than Christian colonisation of super-equatorial Africa, and the development of independent indigenous states to the south. Drawing in part on the ethnography of Africa, his map – inverted to stress its anti-Eurocentric perspective – shows the north littered with sultanates including Al-Magrib (Morocco and its hinterland) which embraces Al-Andalus (Iberia), and the south with states named after the dominant kingdoms or tribes in the area such as Buganda or Wene wa Kongo.

Humour: the 2012 Tsvetkov Map

Bulgarian graphic designer Yanko Tsvetkov became a best-selling author with his Atlas of Prejudice, which first went viral in 2009 and has since been published in English, French, German, Russian, Spanish, Turkish and Italian – and banned in China. His map of Africa shows the continent from a prejudiced US perspective, the only recognisable countries being South Africa and Kenya which are labelled ‘Diamonds’ and ‘Obama’s Birthplace’ (in Tsvetkov’s map of Donald Trump’s view, the entire north is marked ‘Terrorists’ while the south is ‘Obama’s Birthplace’), the rest being designated in huge chunks by some degree of disaster – with the exception of the Arab Spring states which are marked ‘Yay, Democracy!’

Politics: the 2015 Roberts-Swift Map

Journalist Pierre Englebert commissioned cartographers Warren Roberts and Robyn Swift to produce this map to illustrate his article in Foreign Affairs titled “The ‘Real’ Map of Africa: Redrawing Colonial Borders”. Africa’s colonial boundaries have proven remarkably resilient: with the exception of South Sudan and Eritrea, the map has barely been redrawn since the 1950s (Somaliland’s new border with Puntland is in fact a retreat to the colonial-era map). Englebert wanted to represent the regions of Africa where the states failed to exercise effective control over their hinterlands, and for this ‘realist map’, his map-makers consolidated in grey the regions that the French government strongly warned its citizens against visiting. He states: “By my count, of the 11.7 million total square miles of African continental land mass, roughly four million, or about 34%, are out of state control.” As an anarchist negotiating to return to work in that stateless third again, it's a fascinating concept.

[ENDS]

Monday 16 October 2017

Combating Fascism

Members of the Malatesta Battalion of Italian anti-fascist volunteers who fought Franco's forces in the Spanish Revolution.

In 1936, the outbreak of the Spanish Revolution saw perhaps 40,000 international volunteers flock to Spain. There was no internet, cellphone or email communication and travel to the Revolutionary free zone was exceptionally hazardous, and yet they flooded in. Some 250 (later rising to 400) foreigners such as the Algerian anarchist Saïl Mohamed, German IWW veteran Heinrich Bortz and Canadian IWW veteran Louis Rosenberg were organised into an International Group of the Durruti Column, under Louis Berthomieu, which had as its training base the former Pedralbes Barracks, which was renamed the Miguel Bakunin Barracks, and comprised the Sacco and Vanzetti Century (English-speaking), the Erich Mühsam Century (German-speaking), the Sébastien Faure Century (French- and Italian-speaking), and the Matteotti Battalion (Italian-speaking).

Meanwhile, several hundred Italians exiled in France – many of them former anti-fascist Arditi del Popolo militiawomen and militiamen (there was actually an office of the exiled USI in Barcelona at the CNT headquarters) – formed the Malatesta Battalion, nick-named the Battalion of Death, which initially started on the Huesca front under Camillo Berneri, but which went on to defend Basque Country, while other Italians were attached to the Justice and Liberty Century of the Ascaso Column, and after May 1937, Italians formed the 25th Ortiz Division within the Land and Liberty Column. About 40% of the XV International Brigade (incorrectly but popularly known as the Abraham Lincoln Brigade after one of its subsidiary battalions), though it had been organised by the Comintern, consisted of Wobblies and unaffiliated socialists from the USA. There were only four Wobblies and one anarchist volunteer in the Canadian Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion of the XV International Brigade.

The Spanish Revolution brought into sharp relief the question of revolutionary war: whether it was to be fought along conventional hierarchical military lines, or along unconventional horizontal militia lines. Crucially, this was not merely a question of strategy and tactics – though military historian Antony Beevor hailed the militia over the conventional military in Spain – but at its heart also of ideology, the motivating rationale for armed action, and the ethic which mobilises the masses. In the years since the Spanish Revolution’s defeat from within and because of its capitulation to militarisation and statism, and especially during the post-WWII era of national liberation struggles in Asia and Africa and leftist insurgencies in Latin America, the libertarian military option was largely forgotten, and the guerrillas of the 1950s-1980s largely learned their strategy, tactics and ideology from statists, whether Sun Tzu, Guevara, Mao, Giap or others – though the libertarian tendency, although occluded, was never entirely absent from anti-imperialist struggles in much of Latin America, and to a lesser extent, North Africa, North America, and Europe.

Still, the response from the international anarchist movement to not only fighting fascism, but to defending the first significant social revolution since perhaps the true Iranian Revolution of 1978-1979 (not to be confused with the Khomeinist counter-revolution which succeeded it) is disappointing. Certainly, interviews with the anarchists fighting Daesh reveal that the fighters themselves are disdainful of the "armchair anarchists" who criticise those who have taken up arms. Resorting to armed struggle is not a decision to be taken lightly, but just as the struggle against apartheid - in which mass pacifist initiatives such as the Defiance Campaign of the 1950s were popularly successful while remaining largely toothless - a time comes when one has to resort to arms.

But today’s guerrillas, especially those who wish to establish a free society and not merely yet another repressive-exploitative state-capitalist formation, it is a vastly altered battlespace, with hunter-killer drones, cyberwar, intimate satellite imaging, non-lethal weaponry, biometric tracking, over-the-horizon strike capability, 3D-printed weapons, dirty bombs, and so forth. For post-Soviet libertarian communist revolutionaries, therefore, the question of revolutionary war in this new battlespace, or revolutionary neowar as I term it, is urgently framed by new technologies, new post-Soviet ideologies including Salafist terrorism and a revived libertarian communism – and a whirlwind of competing centrifugal hegemonic-imperialist and centripetal decentralist-proletarian forces.

And yet, this essentially asymmetrical war between the poles of what the autonomists Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt call “empire” and “multitude” or what the anarchist Felipe Corrêa calls simply “domination” and “self-management” has been trapped in resistance forms either shaped by a liberal incapacity to grasp the nettle of power (as in the Occupy movement that “occupies” nothing but pre-existing public space), by a naïve, self-incapacitating mass pacifism (as in the Egyptian Spring’s reliance on the theories of the likes of Gene Sharp), and by outmoded tried-and-failed forms of statist guerrilla warfare (in particular the foquismo of Ché Guevara, the militarism of Carlos Marighella, and the proto-state terrorism of the likes of the Red Army Fraction).

A clear question therefore needs to be asked of anarchists, libertarian communists, libertarian autonomists, and all free-associative, decentralist groups, networks and formations: how do we fight back today? How do we ensure that popular mass forces seize power – the ability to transform exploitative relations – and break it down into local directly-democratic, socially pluralistic administrative bodies, horizontally-federated in order to establish a durable libertarian counter-power? I will examine these issues in detail in two forthcoming books and one multimedia project. First the book Deepest Black: Defending the Anarchist Mass-Line (due to be published next year) will examine four historical case studies of mass anarchist movements that defended themselves by force of arms in Bulgaria, Ukraine, Manchuria and Uruguay. Next, the multimedia project The People Armed: Anarchist Fighters Verbatim (a work in progress) will feature in-depth unedited video interviews with anarchist combatants from across the world to be showcased online with text translations and stills portraits. And last, the book Navigating Battlespace: Revolutionary Anarchist Praxis (in planning) which will update Abraham Guillén’s Strategy of the Urban Guerrilla to produce a contemporary anarchist military praxis.

International Freedom Battalion militants pose with their anti-fascist flag in front of a Daesh banner after their liberation of Tel Abiyad from Daesh.

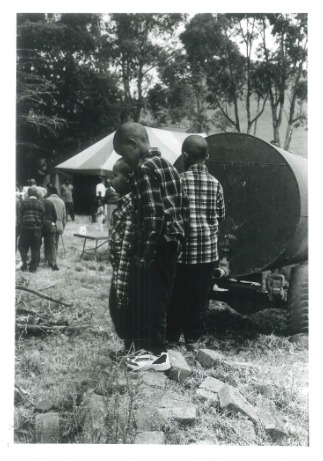

Return to Blydefontein Farm

Two years ago today, I received a cover concept (below) for my book A Taste of Bitter Almonds which featured a photograph (above) I had taken in Eastern Cape many years ago, combined with the image of one of my ancestors of Bengali slave descent. We eventually went with another cover concept, but here is an extract from the book of the story behind that photograph.

BLYDEFONTEIN FARM, EAST GRIQUALAND, 31 MAY 2001

I am standing alongside Madikane Gwiji on the ruined foundations

of the once-proud homestead that his father built, and the memories

of his childhood have come flooding back. He points out to me

the veranda where he and his family once looked out across their

prosperous mealie fields. But, having been evicted when he was

a child, some memories have gone forever: the 60-year-old can no

longer recall which weed-ridden square of bricks was which room.

Gwiji tells me that his great-grandfather, the clan’s patriarch,

whose first name he shares, was a wealthy man. He bought the

998-hectare farm Blydefontein – named after a reliable natural

spring on the land – for his seven sons and two daughters more

than a century ago. The patriarch’s grandson Dunster Gwiji literally

helped lay the family’s foundations for the future: he was trained

as a builder and a carpenter and brought his skills home to the hills

north of Kokstad, in East Griqualand, part of what is today southern

KwaZulu-Natal. Here he built a farmhouse of stone and brick,

designed to last generations. His son recalls that the house with the

sunny veranda was always a hive of activity. ‘It was a very beautiful

house and it was always full of children.’

To one side stood a large barn and to the other a farm school and a

small church, where the devoutly Christian family worshipped while

the Gwijis’ ‘many cows’ chewed the cud on the hillsides behind. For

decades, things were idyllic and the Gwijis were respected by their

white neighbours. Madikane Gwiji recalls that they used to take short

cuts across each other’s land without any incident. But the shadow of

apartheid reached even into the foothills of the Drakensberg. In 1953,

the Gwijis were forced from their home under the notorious ‘black

spot removal’ campaign, an attempt to consolidate land ownership

and occupation along racial lines. Perhaps in grudging deference to

their wealth and title, the Gwijis did not face the bulldozers. Rather,

they were forced into selling their property to a white farmer under

the pretence that it was a voluntary sale. The effects, however, were

pretty much the same: despair and dispersion.

‘It was too bad,’ Gwiji says. ‘I was at school in Kokstad at the

time. Our cattle and agricultural instruments had to be sold.’ Some

implements were left to rot on the land and some were taken by

the government. Blydefontein was divided in two in 1982, with

Mike Rennie, then the owner, selling off a portion to Kippy Bryden.

Dunster Gwiji’s magnificent farmhouse had already been pulled

down. Bryden initially maintained the farm school ‘for the people

around here, a few kids, my children’. But he was later told by the

government to close it, so he knocked the school down too. ‘In 1980,

I took my father to this place,’ Gwiji says, surveying the ruined

foundations of his childhood home. ‘He did not say anything, but I

could see it was painful for him.’

Dunster Gwiji died in 1988, long before his country was liberated,

never knowing the family would ever get their land back. Oddly

enough, it was Bryden’s father-in-law Bill Elliot – grandson of Sir

Henry Elliot, the first magistrate of the Transkei – who acted as

the Gwijis’ attorney as the NP government attempted to force the

family off their land, starting in 1949. At a celebration hosted today

by the Land Claims Commission, the Gwiji family have finally got

Bryden’s portion of their land back. They intend to rebuild the family

homestead. Meanwhile, negotiations continue via the Commission

for Rennie’s portion.

At the celebration women ululate and sway delightedly as

three-legged pots of lamb stew steam. I shoot photographs of

Gwiji youngsters standing in wonder on the brick remains of their

forefathers’ homestead, looking towards the future. Bryden, aged 59,

and his 58-year-old wife Ingrid sit on the stage in the marquee, looking

slightly uncomfortable. Bryden said earlier, while showing me the

extent of the returned portion of land, ‘I’m glad it’s all coming to a

close and I hope the people, when they get it, farm it nicely – but I’ll

help them.’ He said the Gwijis ‘are coming back to where they were.

These are my neighbours and they will be my children’s neighbours.’

[ENDS]

Saturday 14 October 2017

Bonnets and Burkas: the Economics and Ethics of Modest Fashion

Young Breton woman wearing a traditional lace veil in Plougenast, Brittany, photographed by Charles Fréger for National Geographic

This week I walked past what appears to be a new Korean church in my neighbourhood. The doors were open, a man was preaching in a soft gold satin robe and the women - for the congregation appeared to be exclusively black women - were all wearing white lace veils over their hair.

It reminded me of that great scene from the movie Angel Heart when private detective Harry Angel climbs the stairs of an African-American church in Harlem and the door swings open to show two young black girls, apparently demure novices in their sect, dressed in ivory dresses and lace-trimmed wimples. In 2014, National Geographic - my favourite journal; I boast a collection going back to 1915 - ran a photo-feature by Charles Fréger on the traditional lace head-dresses and silk bonnets of Breton women. Unlike South Africa where the wearing of the Voortrekker bonnet is pretty much reserved for your wizened octogenarian maiden aunt whose mother survived the British concentration camps, what struck me about Fréger's work was how young so many of his models were.

Now, there is a complex relationship - in which I confess I am not expert - between young people and traditionalist dress, particularly in regions with separatist aspirations such as Brittany, or Basque Country, or Kurdistan for that matter. In Brittany, I am aware of the anarchist organisation called Unsubdued! (Desuj!) which was founded 16 years ago, but which presumably has a primarily young membership, but I have no idea what their political-sartorial perspectives are; most likely, their idea of covering the face is with a black balaclava!

And yet, whether it is in allegorical form - as with the TV series based on Margaret Atwood's novel The Handmaid's Tale, in which de facto brood-mares for the ruling neo-Calvinist elite all wear body-length scarlet dresses and white bonnets - or in real life, on the street, what is termed "modest fashion" is making somewhat of a comeback.

In June, Vogue featured 19-year-old Somali model Halima Aden as its first-ever hijab-wearing cover model, driving her Instagram account up to 182,000 followers, while the mainstreaming of modest fashion stores like Ajmaan in Rosebank indicate that a sea-change is occurring in high-street style.

In February, London hosted its first Modest Fashion Week at the Saatchi Gallery, featuring more than 40 labels. In March, Nike announced its sleek Pro Hijab athletics-wear for Muslim sportswomen will be available next autumn. Even Forbes took notice, writing that luxury brands such as “DKNY, Tommy Hilfiger, Oscar de la Renta… have produced special collections for the Ramadan holiday… In January, Dolce & Gabbana released a collection of hijabs and abayas.”

This shift is not driven by fashionista fancy, however, but largely by the dramatic emergence of wealthy Muslim youth: as Harriet Sherwood wrote in The Guardian last year, “Muslim minorities in Britain, Europe and North America are young, affluent and growing… the Muslim pound, like the pink pound before it, will force soft cultural change by means of hard economics.”

Thomson Reuters’ State of the Global Islamic Economy Report 2016/2017 noted that Muslim spending on clothing and footwear soared to US$243bn – benchmarked against a US spend of US$406bn – with US$56bn spent on cosmetics; and expenditure is projected to hit US$368bn and US$132bn respectively by 2021. At the core of Muslim spend is the US$44bn spent in 2015 by women aged 15 and above on fashion excluding footwear.

“Modest Fashion is gaining mainstream interest,” the report said, “with several retailers and brands such as Dolce & Gabbana, Uniqlo and Burberry entering the industry and several notable investments driving the sector forward...” The industry, it noted, is centred on the United Arab Emirates, but key producers include Turkey, China, India, Italy, Sri Lanka, Bahrain, France, Singapore, and Togo.

The rise of Muslim – and more broadly conservative – fashion has been apparent to rag-trade observers for some time, not only in its core markets such Turkey, the largest consumer of Muslim fashion in the world at US$25,7bn in 2015, and Nigeria which purchased US$16,1bn the same year, but also perhaps counter-intuitively, in countries such as the USA, though Thompson Reuters notes that the Western market is underserviced, and is threatened by hijab bans such as that in France.

Modest fashion appeals to conservative Christians and other traditionalists too, but it was sassy, tech-savvy young bloggers of “Generation M” – the almost one third of the world’s Muslim 1.8bn population aged 15 to 29 – who over the past few years have ensured that modest fashion lighted up on the radar of global haute couture.

So says Shelina Janmohamed, London-born author of the book Generation M: Young Muslims Changing the World, who singled out Muslim bloggers like the British-Japanese Hana Tajima and the Kuwaiti-American who goes by the handle Ascia AKF who “built loyal followings among young Muslim women. As such bloggers grew in popularity they started their own labels, and the modest fashion industry was born.”

Thomson Reuters’ report backs this up, noting that Muslim Millennials’ primary social media engagement with the global Islamic economy were in finance, media and entertainment – and modest fashion, the latter with 101,000 Facebook interactions per year.

Much of the trade itself occurs online, as via the UK’s 250-designer modest fashion portal Haute-Elan, while in South Africa, My Online Souk, founded four years ago by Sabeena Khonat, now 40, digitally showcases funky modest styles in everything from swimwear to corporate dress, 85% of its brands sourced locally.

Her sister and partner Jehan Ara Khonat, 26, told me that the core of their client base was women aged 25-35 – and that it was growing beyond the Muslim community, “appealing to every type of modest dresser.”

“I follow quite a few global modest fashion figures, mainly on Instagram and YouTube, but there’s some great local talent too such as Nabilah Kariem and Aqeelah Harron of Fashion Breed. They inspire me, just as they inspire others of creative ways to look great without compromising your values.”

And modest fashion’s potential market is only growing: the latest Pew Research Center figures suggest that Sub-Saharan Africa alone will account for almost a quarter – 24,3% – of the world’s projected 2,76bn Muslim population by 2050.

And yet, not all modest fashion is restricted to the Muslim world: my Catholic wife of many years back loved the idea of the Spanish mantilla, a lace veil held high over the head with an elaborate comb often carved out of mother-of-pearl, though she was happiest in a bikini top and camo shorts; and of course one recalls denominations like the Amish with their emphasis on "plain" clothing - though Vogue hopped on that horse-cart too, running an Amish-inspired Stephen Meisel fashion series in 2009.

I had quite a debate with a friend while writing this piece as she views the term "modest fashion" as pure code for restrictive burkas and niqabs imposed on women by Salafist fascists. But that reminds me more of the reactionary British tabloids freaking out over celebrity chef Nigella Lawson wearing a "burkini" to the beach in 2011; her choice as a woman became totally irrelevant in that shit-storm.

As an atheist man from a society where "liberated" women are highly sexualised, I am at somewhat of a disadvantage in this discussion, especially as I have Muslim women friends who are definitely, totally anti-Salafist and very progressively minded but yet who wear the hijab, either because it is simply the cultural norm in countries like Morocco where they live, or because it actually does express the convergence of their faith with fashion. Surely we can be happy with what makes them comfortable in their own self-expression?

[ENDS]

Thursday 12 October 2017

Be Cool, Stay Sick and Turn Blue!

Although it is usually recognised that rock 'n roll emerged from the delta blues, people seldom go further back, beyond New Orleans of a century ago to examine the roots of the music in the Caribbean, on the island of Hispaniola - today Haiti & Dominican Republic - where the cultures of Central and West African slaves merged with that of Irish slaves deported as pagans by Cromwell. The story is beautifully told by Michael Ventura in his inimitable essay Hear That Long Snake Moan. Beyond the music itself, I love that some of our most common words in rock 'n roll slang are actually derived from Africa - and love repeating the story at length in bars (so you are forewarned!). Many of the terms, like "cool" for example, have a far deeper and more complex meaning that Africans should recover, understand and deploy. Partly because of this fascination, I started compiling a dictionary of words associated with rock 'n roll and the psychobilly subculture. Enjoy!

Psychobilly Dictionary (a work in progress)

Rockabilly = a form of rock ‘n roll usually played by only three musicians, wielding a stripped-down drum-kit (base, snare, side, high-hat), a steel-stringed lead guitar (sometimes even a 12-string), and a stand-up bull bass, usually played to a fast staccato rhythm.

Psychobilly = a form of Rockabilly that explicitly draws in its lyrics, mood, and style from the B-movie horror and suspense film genre of monsters and mobsters.

Billydolls = rockabilly and psychobilly dames, usually effecting either a retro ‘50s look or more outrageously morbid dress as in Vampira.

Knif = a reversal of fink, a US term meaning punk in its original sense, an undesirable person, a low-life, and like punk, adopted as a rebel self-descriptive.

Stay sick = in typically inverted psychobilly cant, it means stay awesome, stay true to the psychobilly way of life; as with the phrase below, it has the virtue of being eight letters so readily tattooable on the knuckles.

Turn blue = turn your back on the conservative norm, reject square life.

Square = the nature of the conventional world and those who inhabit it, unable to think outside of the box.

Stilyaga = style-hunters, Russian psychobillies of the 1950s, defiant of grey Stalinism, not to be confused with the fictional Russophile "Droogs" of A Clockwork Orange who owe more to skinhead subculture.

Kaminari Zoku = Thunder Tribe, Japanese psychobilly gang of the 1950s, the name derived from the roar of their motorbikes.

Canary = a female torch-singer, as in she sings like a canary.

Dudes = city slickers, urban dandies in cool duds.

Hep = from the Wolof term hepi, meaning in the know, streetwise, enlightened and worldly, later mutated into the be-bop term hip.

Cats = psychobilly dudes, affecting the languid, aloof attitude common in domestic cats, the feminine of which is kittens.

Betties = psychobilly kittens with their hair banged in Bettie Page style.

Juke = from the Mandinka of Mali, meaning bad, in the sense of an unrighteous (ie: irreligious) person, thus a juke joint is an unrighteous place.

Boogie = derived from mbugi, a word of the Ki-Kongo of the Congo, meaning devilishly good.

Mojo = the Ki-Kongo word for soul, meaning invested with transcendent, healing spirit power.

Cool = from the Yoruba of Nigeria, meaning self-possessed, exhibiting grace under pressure, and a sophisticated, calm-yet-audacious representation to the world.

Subfuck = underwhelming, nowhere near up to scratch, the opposite of cool.

Funky = derived from the Ki-Kongo word lu-fuki, meaning a healthy sweat, as in that worked up by dancing or working on your hotrod.

Dropped and chopped = a hotrod made from a vehicle that has had its suspension lowered to almost scrape the ground (dropped), and shortened (chopped).

Shaved = a hotrod that has had all its door-handles and other protrusions removed to provide a smooth profile.

Lead sled = a big gas guzzling hot-rodded sedan, dropped so that it rides like a sled, but unchopped.

Rat rod = a hotrod that is deliberately not polished up but rather left with its natural patina of rust and chipped paint, often augmented by whimsical psychobilly items such as moonshine barrels or hatchet gearshifts.

Witchdoctor = a member of the clergy, a jungle piss-take on the religious square.

Jungle = a rhythmic African drumming technique based on the congas, signifying a wild abandon (yes, this way predates Tricky!).

[ENDS]

Monday 2 October 2017

Sixties Japanese Anarchism

The anarchist movement was established in Japan in 1906 during the late Meiji Restoration, the political, social, military and economic modernisation period. Initial dramas such as the 1911 treason trial in which anarchists were executed for plotting against the "god-emperor" gave way in 1926 to the formation of an anarcho-syndicalist trade union movement, the Zenkoku Jiren, at 8,400 members, the country's third largest labour federation. The movement narrowly survived the rise of ultra-nationalism and fascism in the 1930s and world war in the 1940s, establishing a tiny 200-member Japanese Anarchist Federation in 1946. The following is a synopsis I have just finished writing of the movement in the 1960s.

In Japan, 1960 proved a hot year of struggle with miners arming themselves in a doomed bid to prevent the pit closures at Miike, while post-war parliamentary democracy endured its severest crisis of confidence so far when the ruling Liberal Democrats backed by a strong police presence, rushed the unpopular Security Treaty, or military alliance with the USA, though the Diet in which they held two-thirds of the seats. By then, the formerly communist student Zengakuren was dominated by anarchists and Trotskyists according to Edwin O. Reischauer, but by Trotskyists, Maoists, independent Marxists and non-sect radicals and only a small current of anarchists according to Tsuzuki Chushichi. In revolt against the Security Treaty, the Socialist Party-allied Sōhyō worker’s federation and other unions staged mass protests which brought 4 to 6-million out on strike; the Japanese Anarchist Federation (NAR) journal Kurohata (Black Flag) urged a general strike and, in synch with the Zengakuren, a shift from peaceful protest to open violence against the state. The movement faltered and failed, but as Tsuzuki notes, “belief in parliamentary democracy was now seriously shaken, and the gap between the militants and the existing left-wing parties was now unbridgeably widened…”

Tsuzuki writes that from among the anarchist ranks at this time emerged the theorist Ōsawa Masamichi who had joined the movement after the war and who argued in the pages of Jiyū-Rengō (Libertarian Federation) which had taken over as the NAR paper, that, in Tsuzuki’s words “the upper rather than the lower, strata of the proletariat would fight for the control, rather than the ownership, of the means of production; multiplication of free associations communes rather than the seizure of political power would be the form of revolution… revolution would be cultural rather than political, and arts and education would play an important role in it.” Ōsawa’s gradualist and evolutionary approach was rightly attacked as reformist within the movement. But although the failure of the general strike sowed confusion in the Zengakuren, the outbreak of the second phase of the Vietnam War in 1965 proved electrifying to the radicalised Japanese students as it was seen as a harbinger of a coming total war, with Japan being drawn into supporting South Korea which in turn directly sent troops to fight the communists in Vietnam; anti-war sentiment fed powerfully in Japan on anti-militarist and anti-nuclear radicalism.

A new working class organisation, the Hansenseinin-i, or Anti-War Youth Committee, drew together young trade unionists and Zengakuren students in a series of direct actions against the war; despite being founded by the Socialist Party, the Hansenseinin-i developed into a movement that took a stance against the formal politics of the Socialist Party and its Sōhyō union federation; but though it was prepared to fight in the streets, “Direct action in the factories was left in the hands of more professional revolutionaries, the anarchists,” Tsuzuki writes, in particular of the Anti-Vietnam War Direct Action Committee, or Behan-i, which consisted mostly of anarchists and which raided munitions factories in Tokyo and Nagoya, publishing details of the Japanese munitions industry as “Merchants of Death”.

Although the Behan-i was criticised by some anarchists for offering a “prelude to terrorism” and it soon folded, it had at least raised the militant profile of the movement among the Zengakuren. By 1967, the Zengakuren had somewhat stabilised into four main blocs – the Kakumaru which was dominated by Trotskyists, the Sanpa which blended Trotskyists, expelled communists and socialists, the remnant communist Minsei, and the non-sect bloc lead by the physics graduate Yamamoto Yoshitaka whose politics were described as “self-negation”, “a subspecies of anarchism,” according to Tsuzuki, quoting Shingo Shibata. Yamamoto came from the Tōdai-Zenkyōtō, the Zenkyōtō, short for All-University Council for United Struggle, being a loose network of anti-communist radical groups that “sprang up in each storm centre” of the emergent student struggles against authoritarian university and hostel management, and other ills of a system seen by students as being a mere mass-production plant for capitalist ideology.

By this stage, Tsazuki argues, the revolutionary student movement was influenced by the likes of the “anarchist intellectual” and Behan-i supporter Yoshimoto Takaashi, the son of a shipwright who theorised the political state as both the apex of the “evolution of religious alienation” and a pure expression of ultra-nationalism; against this, Yoshimoto proposed a classless solution in which intellectuals expressed the desires of the silent masses. Another key figure was the dissident Marxist Hani Gorō who argued for a network of autonomous socialist cities to replace the state. But, as Tsazuki cautions, despite many anarchistic calls for direct democracy and direct action, the student movement was so ideologically eclectic that it was “more nihilist than anarchist”; in fact, its unbounded extremism saw outgrowths of both terrorism like that of the Japanese Red Army, and even of neo-fascism.

In 1968, the Zengakuren was able to mobilise mass demonstrations against a proposed visit to Japan by US President Dwight D. Eisenhower, against the dispossession of peasants for the construction of the new Narita airport, and against the docking at Sasebo of the US nuclear submarine Enterprise. Zengakuren radicals wearing helmets painted with their sect’s colours and wielding staves regularly clashed with heavily armed riot police, the demonstrations peaking in June with hundreds of thousands of students, workers, housewives and shopkeepers out on the streets, and about 55 universities occupied by their students. Despite the demonstrations being very orderly, with only one death reported (an accidental trampling of a female student), a nervous US government cancelled Eisenhower's visit.

In 1969, the Zenkyōtō in various “storm centres” united into a national federation – but the Japanese Anarchist Federation dissolved itself: Tsuzuki says it would seem curious to an outsider for the NAR to disband “at a time when militant students were determined to defend their ‘fortress,’ the Yasuda Auditorium at Tokyo University, against an attack by the riot police. The anarchists themselves called the dissolution ‘a deployments in the face of the enemy.’ Yet they had to admit at the same time that they had reached a deadlock in their attempts within the Federation to formulate new theories of anarchism and to hit upon new forms of organisation for the new era of direct action which they believed had begun.” Although the NAR failed, anarchism remained a persistent minority current on the Japanese ultra-left: in 1970, the Black Front Society (KSS) was founded, followed by a Libertarian Socialist Council (LSC), while the old “pure anarchist” Japanese Anarchist Club (NAK) which had been founded in its split from the NAR in 1950 continued publishing its journal Museifushugi Undō (Anarchist Movement) until 1980.

* And for some visual ideas of what the Japanese varsity occupations looked like back then (makes the South African ones of recent years seem tame): https://vimeo.com/235615382

[ENDS]

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)